By Tyler Campbell

Photographs by Ronald Gray

“Come celebrate with me that everyday something has tried to kill me and has failed.”

― Lucille Clifton

“Kids playing on the stoops wearing Dungarees

Unbeknownst to them, they living in

The city under siege”

— Black Thought

Drew Williams knows a thing or two about surviving in the streets of Philadelphia. Now 33, he spent much of his adolescence in North Philly, hustling and selling drugs in between two separate stints inside federal prison on drug-related charges.

When I met up with him outside of YOLO Cafe, a community hub and local late-night spot in North Philly, he told me of his time in the streets: “It’s tough out here. I been shot … seen my whole life flash before my eyes. I been in shootouts. Too many to count. I lost friends, 20 maybe 30. I’m at the point now where I accepted that I might die out here.”

Young Black men like Drew are the face of gun violence in Philadelphia, as both victims and perpetrators. More than 72% of people now in city prisons and 85% of those shot in Philadelphia are Black, even though Black people account for just 40% of the city’s population, city and census data show.

Both the violence and the racial disparities are, unfortunately, nothing new. What is new, though, is the recognition that the city’s gun violence epidemic is a public health crisis — one of its worst ever (even if city leaders remain in denial).

More than 550 people were murdered in Philadelphia last year — making 2021 the city’s deadliest year on record, surpassing the record-breaking 500 homicides it tallied in 1990 at the height of the crack epidemic, and then again in 2020. According to city data of all the shootings in 2021, 75% of the victims were Black men, a quarter of whom were between the ages of 18 and 24.

Since January 2021, in response to all of the hurt and loss I’ve witnessed in the city, I made it my mission to speak with men like Drew who were born and raised in the city, to share their stories of living under the daily threat of gunfire and surviving in Philadelphia.

There’s a reason I always tell my homies “be safe” after every interaction. Growing up in Philly, there is this unspoken knowledge that each time could be the last time we see each other. The threat of losing someone you care about to gun violence — or prison — is ever-present.

Despite how long gun violence has plagued Philadelphia, local leaders have made little progress in reducing it. In fact, both Mayor Jim Kenney and Gov. Tom Wolf have yet to officially declare a state of emergency — even though Philadelphia City Council demanded it last year and public leaders around the country, including in New York and Flint, Michigan, have taken that step.

While some remain skeptical about how an official declaration would actually help the city’s most vulnerable communities, one thing remains clear: Gun violence is a complex issue that lies at the intersection of generational poverty, unaddressed trauma, lack of community resources, underfunded public schools, and decades of institutionalized racism and sheer neglect. A complex crisis can’t be fixed with the same old simple ideas — community briefings, cease-fire marches, and new basketball courts.

Lost in the calls to action and gruesome headlines are the real lived experiences of young Black men in communities where gun violence is not a news story, a tragic anomaly, or a talking point for evening news anchors, but a routine fact of everyday life.

I first started interviewing men like Drew on the heels of Philly’s most violent year in decades. But after my first interviews, the piece quickly evolved from a story about the city’s gun violence crisis to one about survival and kinship, love, and perseverance. I wondered what would happen if, instead of focusing solely on Black death and the perils of growing up in Philadelphia, we celebrated the lives and experiences of those on the other side of the statistics and headlines?

For this project, I wanted to give fellow Black men the chance to speak for themselves and have their voices heard. Below are excerpts from my conversations with them lightly edited and condensed for clarity. For several, it was their first time ever being interviewed about their lives and experiences.

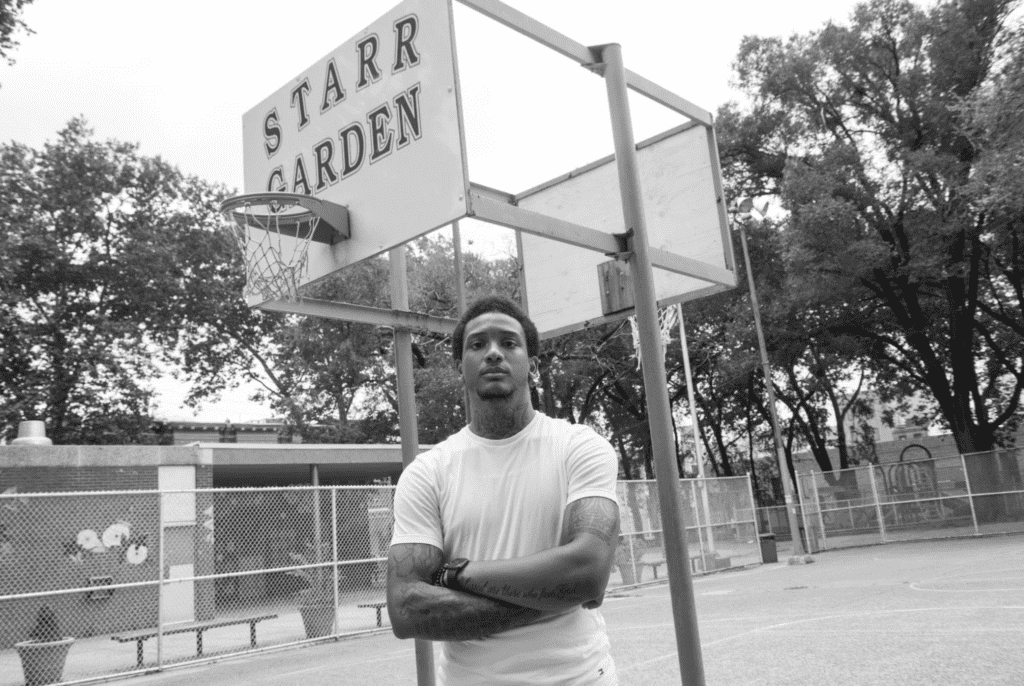

Drew Williams: ‘You have to want better for yourself’

Drew Williams is like a celebrity on his block, flashing a wide toothy grin and throwing a handshake to damn near everybody who walks past. It’s evident he’s no longer the same young kid who ran these streets carrying guns and selling drugs. But Drew, like other Black people who share the label “felon,” is routinely reduced to his criminal record, and people who don’t know him personally often make assumptions about his character based on his past.

“[I’m] Black. From North Philly. Sold drugs. Been to prison,” he said. “Especially [when] they see my tattoos and how I dress, they going to think the total opposite of who I am. I’m respectful, I got manners. I take care of my people. And looking at me I know nobody wouldn’t ever think that.”

The photographer and I met him on a hot summer evening, when it felt like just about everybody in the city was outside.

Drew is most in his element when he is among his people on his block. From what I observed, people in his community seemed to not only know him, but respect him. As the three of us scouted places in the neighborhood with optimal lighting for Drew’s photos, it felt like he was approached by someone he knew every 30 seconds.

Of course, the love he receives today doesn’t capture the full harm his drug-dealing past caused the people of this same community. But to Drew, defining a person as good or bad isn’t always so black and white.

“Knowing I’m doing wrong, I always try to do some good for the people out here, too.”

Giving back [and] looking out when I can. Christmas or Thanksgiving come around, I always take care of the community,” he said. “The same community I’m taking so much from, I made sure to give back and thinking I’m doing a good job, that’s going to make up for all the wrong I did, when in reality, [it] can’t because the devastation is just unmeasurable. But I’m learning and growing. I used to say, ‘If I ain’t doing it, somebody else is going to do it.’ But that’s not true. You have to want better for yourself.”

Growing up in an impoverished community like Drew’s North Philly neighborhood leaves some people with few opportunities for upward mobility. It wasn’t laziness that drove Drew to first start selling drugs because, as he put it, “I always had a hustling spirit within me.” But with Pennsylvania’s minimum wage at $7.25, bagging groceries or working the drive-thru at Checkers wasn’t enough to support him and his family.

To become the person he is today, Drew had to outgrow his own mindset, which was solely focused on survival. After his second stint in prison, Drew knew it was time for a serious change before he ended up as another casualty of the streets.

“For me, it’s a poverty mentality, man,” he said. “Everybody trying to make it out of here. I always look at it as the crab in the barrel …You trying to make it up out this jawn and really trying to survive, and you just never know what’s going to happen. Pretty much, everything the streets teach you is about surviving. How to take care of self first.”

Putting himself first was the only way Drew could outsmart the drug game and not meet the same tragic fate as many of his peers.

“I see the streets for what it is … something designed to never let you fully win. It’s just a trap,” he said. “That’s why a lot of people call it the ‘trap.’ Cause it’s literally a trap out here.”

Mike White: ‘People judge you based on your charges’

There is a lot more to Mike White than what the headlines say. In 2018, he was arrested for the fatal stabbing of a real estate developer. Since being acquitted on all charges, things are looking up for the South Philly native — he has since started online classes at the Music and Production program at the Los Angeles Film School and recently became a father.

Life now is a far cry from the jail cell where he spent his 21st birthday.

“Everything in my life has literally gotten better since that point. I think I reached that lowest point of my life at such a young age because I was supposed to see the blessings on the other side. And when I really sit back and I think about it, I’m thankful for the moments. Because if I didn’t go through all of that, I probably wouldn’t value life as much as I do now.”

I knew Mike when he was a student at the Academy at Palumbo and one of the best young poets in the city, ripping mics every Friday in the New Freedom Theater off North Broad Street.

A 72-second encounter in Rittenhouse Square drastically changed his life. The incident, along with a failed suicide attempt at 17, were two of his life’s “lowest points.” His strong will and the support of friends and family got him through his trial.

“I can’t even put into words how tough my trial was. Just mentally, physically, emotionally. But I got through it, and that’s when I [knew I] literally can do anything I want in this world.”

When I asked how gun violence has impacted his life, he paused and said, “With all the things I’ve been through and the things I’ve seen, I don’t even like talking about guns. It’s to the point where I don’t even want them anywhere around me.”

The first time we were scheduled to talk last spring, we had to reschedule because Mike and a friend got in an argument in which guns were pulled on them. Mike thankfully was able to de-escalate the situation. When I later caught up with him, he told me he doesn’t fear death because he knows he has a higher purpose.

He talked about his upbringing in South Philly and how it shaped his ambitions for the future.

“Growing up in South Philly was great. I loved my block because I used to live right next to the papi store. It was sweet. Every day I was in that jawn. I used to get two white glazed honey buns, a bag of Doritos, the cool ranch and blue Big Burst to drink. That would be less than $5, and I would bring the change back to my mom.”

The corner store next to his house was as far as his mother would let him go.

“It was a Chinese store around the corner at 23rd and Mifflin and after a certain time, my mom wouldn’t let me walk to that Chinese store because somebody always was getting shot over there, and there was always police around. When I got older, I learned she knew somebody who got killed right outside of that store. So I took her advice and just didn’t go around that way.”

A gifted cultural translator, he possesses the unique ability to transmute his hardships into gold nuggets. Mike uses his poetry-writing talent to create music now, but he doesn’t just rap. He makes beats for his own label, Limitless Records. His sound mixes spoken-word poetry and hip-hop, with a distinct Philly swag — a grittiness you can hear when he raps. For months when the pandemic first started, he’d spend all day writing rhymes and plotting ways to make his record label successful.

Studying music at college is his chance to blossom into the artist and creative he was destined to be when I first saw him perform on that stage in North Philly. It’s his first time taking college classes since he was arrested in 2018. He’s excited to eventually leave the city where he’s lived all his life. He’s been through too much hurt and loss, he says, and feels a move might be healing.

“Because when you go through what I been through, people judge you based on your charges. And, yeah, I’m on probation because of a tampering with evidence charge, but people look at me like, “Oh, well he’s a murderer.” Like, nah, that’s not me. I’ve never been that type of person. I’ve never been on no killer shit. I’ve never been on no street shit. It’s just the stigma that come around an incident like that, they be like, ‘Oh, you killed somebody so you’re a killer.’”

Still, in a way, he can appreciate the hardships he has endured.

“If I just ignored all the trauma and all the things that I went through, all the things my family went through, I probably wouldn’t be as smart, as intuitive, as thoughtful and … I wouldn’t have the mindset and outlook on life that I have now.”

Sadiq Sellers: ‘Ain’t nothing cool about your mom crying’

Sadiq Sellers spent much of his adolescence pushing drugs in North Philly. He hustled the streets back in 1990s, when Philly first saw 500 murders within a single year. Sellers first went to prison when he was 20 years old for third-degree murder. Now 43, he’s home from an 11-year stint in federal prison on drug charges, after spending the better half of his adult life inside a cell. He’s ready for a fresh start.

“I didn’t think I’d live to see 18. A lot of my friends got cut down before they had pubic hair. So gray hairs, I embrace mine.”

Sadiq still lives on the same block on Douglas Street where he grew up, but it feels different to him now.

“When I grew up we didn’t have much, but there was a real sense of community. What little we had, we shared. So the loyalty between us, it was tight.“

His fondest childhood memories were those where he and his siblings “created fun,” playing in Fairmount Park near his home, from sun up until the street lights came on. Made-up games like Halfsies, a variation of baseball using a broomstick and half a tennis ball, and Doorbell Dixie, a ring-and-run prank. North Philly felt like more of a community then, with a sense of togetherness he just doesn’t see in the city anymore.

Sadiq has lost countless friends to gun violence or life sentences in prison — but that’s just what comes with the drug game, he said.

Sadiq said he first began to carry a gun after someone pointed a gun at him after a fistfight outside a local chicken spot in 1996. He saw his gun not as a weapon to cause harm but instead as a means of self-preservation. An old hood proverb remains true to this day for many young Black men living in the city: “I’d rather get caught with it, than without.”

“Where I’m from, you don’t take threats against your life lightly,” he said.

Looking back, he admits he armed himself because of “stupidity, pride, and ego.”

“I hated guns growing up. I really didn’t want anything to do with them. I was really into boxing, but my people always had easy access to guns, and after he threatened [me], I feared for my life.”

Soon after, Sadiq ran into a guy who owed him money. He shot and killed him — a decision he regrets, but doesn’t make excuses for. His lawyer was able to get the charge reduced to third-degree murder, and Sadiq ended up doing eight years.

Sadiq now works at a meat factory chopping steaks for grocery stores and, on weekends, he cuts hair out of a barbershop he set up in his living room.

Any half-decent barber is as good at conversation as cutting hair. And Sadiq speaks with an unexpected brilliance, shifting easily between topics like gentrification, the city’s shortage of opportunities for young people, prosecutorial misconduct, and the proper way to cook a lobster at home. He’s compassionate with a critical consciousness about what is happening around him.

“Everybody in the inner city not animals. It’s just a small percentage of people who are criminals. But that’s what’s getting highlighted. Those are the misconceptions, because you have a lot of community members who are doing real positive stuff. Ms. Doris Johnson Concern Care Center. That’s a community center that I grew up in as a child. She would provide jackets, meals, canned goods. In the summertime, you can go get free lunches and learn about opportunities and resources. There still is that camaraderie in the inner city. Why do you think that gentrification rates are so high? People [are] coming back for a reason, not just because it’s easily accessible to Center City or for the nightlife. It’s because these inner cities, they’re beautiful. And they just need time and love back put into them.”

“They need somebody to invest in them. That’s the big misconception about North Philly, West Philly, South Philly. There’s still love and camaraderie in those places. But one thing about news and the media, violence, and crime, it just excites something inside of the people and it’s interesting.”

“Still, take it from me, there ain’t nothing cool about that [when] your family member’s on a T-shirt, or when your mom crying.”

Kharon ‘Bonk’ Randolph: ‘I hope to lead by example’

The first thing out of Kharon’s mouth when you talk to him is how much he loves his family. He proudly says it with a smile that’s contagious. He tells me excitedly how his little brother Kam is a freshman in high school and they’ve been working on his jump shot together nonstop, so one day he may be an even better player than his big brother.

The eldest of four, Kharon is a family man. Now a senior studying psychology and sports medicine at Holy Family University in Northeast Philly, where he is also the starting point guard on the basketball team, he is starting to think about what life could be after graduation. He doesn’t plan to leave the city. He knows his younger siblings, as well as kids coming up in his community, need him — and his psychology degree — too much. He wants to “bring awareness to what mental health is … why it’s important and how it can help overcome the trauma you [are] going through.”

He wants the young kids in the city who grew up like him to have more opportunities and role models capable of giving both good advice and tangible things like a ride home from school or help finding a summer job.

Talking to Kharon about his plans gives me a kind of hope for the city — not the fake, played-out Obama-type of “hope” that politicians spew every election cycle. Instead, Kharon gives me hope, as he talks, that he truly is capable of bringing the change he envisions. His dreams feel like prophecies of things to come because of the way he says everything in a confident and matter-of-fact tone.

Kharon acknowledges that he grew up better than most of his peers, first in Southwest Philly and later, the Northeast. He stayed on the right track because he grew up in a supportive, two-parent household where both parents worked and his father and uncles served as positive male role models.

“Growing up in Philly, you’re not really a kid. That was a reality check for me. Just seeing kids that was in my fourth grade [class] that was selling drugs just to provide for their family.”

Seeing kids that young resort to selling drugs to support their families gave him an empathy many people don’t have for us Black boys.

“It’s hard for me to fault anybody that does illegal things like selling drugs or stealing things to try to provide, because it’s a survival tactic, a survival mindset. If you don’t do those things, where you really gonna be at? What will you really have?”

Just before starting at Holy Family, he learned his childhood best friend, Sabree, was shot and killed. The loss left Kharon feeling more alone than ever. It was “100% the toughest thing I’ve ever had to survive.” Sabree, whom he regarded as a brother, died over a few hundred dollars in a robbery gone wrong.

All young Black men who grow up in Philly, including Kharon and me, know deep down that we all could have been in Sabree’s shoes, and vice versa. In that way, there is a strange sort of kinship built between the victims of gun violence and those of us who — by sheer luck — survive. Years after Sabree’s murder, Kharon still struggles with survivor’s guilt.

“I kept thinking what could I have done different? … [I know now] I couldn’t do anything about Sabree’s situation, [but] I can do something about people that are just like him. I relate to these kids too much. They don’t really got too many people where they could be like, ‘Yo, he was me at one point.’ Kids need to see that … that can really change lives.”

Kharon is a skilled basketball player, one of the most underrated to come out of the city in recent years. He wants to bridge his love for the game with his desire to help the next generation by opening up a rec center for young kids from all over the city.

But his vision isn’t your typical rec center where kids just work on their game. Instead, Kharon wants to create a dynamic community space that provides life-skills training along with mental health services to help them recover from their traumas. He sees helping kids like Sabree as a way to honor his friend’s memory while also reducing the stigma surrounding mental health in the Black community. He envisions keeping his rec center open as late as midnight, seven days a week, so that it becomes a safe haven for kids who feel like they have nowhere else to go.

“I’m passionate about helping people. I hope to lead by example just to show kids what they can be … [because] they don’t know what they never seen. I’ll be the second person in my family to graduate college, but the options open to kids is limitless. We just have to show them … Nobody as a kid wakes up from a dream and say, ‘Oh, I just dreamt about wanting to be a drug dealer, a killer, or a scammer.’ People just do it because they in survival mode. Poverty causes all of this.”

“I don’t think real change starts with them [politicians] downtown, but from within. It starts with us. We the ones living in our communities everyday and we not going to trust nobody from the outside to come help us … We know what we need best, always.”

Eli Capella: ‘Every kid I teach, every song I make, stops a person from carrying a gun’

The late great Nina Simone said, “The job of the artist is to reflect the times.” Eli Capella embodies that famed quote.

A full-time creative and recording artist, Eli has put out two mixtapes during the pandemic that garnered thousands of plays online: “Quarantine Dreams” and “She Can’t Save Me.” The projects helped him cope with his depression and suicidal thoughts while also uniting people who are struggling with isolation through the pandemic.

“I always thought people with suicidal tendencies were weak-minded, but what I learned is it’s really the people that are strong-willed that go through it. ‘Quarantine Dreams’ was my response to my own depression. The whole ethos of that jawn was just ‘work with what you got.’”

Eli is unique when it comes to the sound and style that inspires his music. Unlike many young Philly rappers who grew up on the sounds of 2010s hip-hop artists like Lil Wayne, Chief Keef, and Meek Mill, Eli draws inspiration from a wide variety of genres, everything from ‘90s R&B and soul, classic rock, electronic, and Afro beats. The result is an up-tempo yet deeply introspective style of rapping unlike anything else on the Philly scene, which is now saturated with drill hip-hop artists.

When he’s not making music, he is a youth mentor and educator “working with kids with a program I started called ‘Why Tunes.’ It’s a recording artist therapy program where you don’t have to be an artist to be a part of it, but it really helps children be able to self-identify internally and externally with things that go on, on an emotional level, on a societal level. So they get to learn about themselves while making music.”

He knows the unique challenges and peer pressures that come with growing up in a city that can be, as he put it, “extremely demanding,” in terms of its reputation for toughness. Many young people — especially young men — don’t “really have time to just think and ponder on good decisions or bad decisions. To survive in Philly, you have to have a lot of grit. You have to be able to understand that nothing is personal. People who aren’t from here might feel like people from Philly is mean. And that’s nothing personal.”

Eli has found himself in the crosshairs of a gun several times, both by people who look like him and at the hands of police.

“I was walking back home to my pop crib when I was living with him up Kensington-Allegheny, and it was this boul, you could tell that [this guy] was high off wet. He was real aggressive, real hard. That’s what it do to you. He was talking to himself and I happened to be walking behind him. He got paranoid just out of nowhere and he pulled a gun out and was like, ‘I’ll blow a motherfucker’s head off right now!’ I didn’t panic, I just swerved and like, walked to the other side of the street. And I walked in my dad crib like, ‘Yo, dad, like I almost got shot! This crazy.’ But it was so normal though.”

One of the things he stresses with his young students is that leaving the city will not solve their problems. “Anytime we think of violent places, we think of moving as the solution…I’m surrounded by Black people who have the potential to be leaders … That’s just not true because there’s hope in everything that goes down. Every kid that I teach, every song that I make, stops a person from carrying a gun. If I’m on that stage and you two-stepping, and you waving your hands and you enjoying it, that’s one less person that’s thinking about robbing somebody. Even if it’s for five minutes of my set time, I’m doing my job.”

If you have been affected by gun violence in Philadelphia and need help, visit: UptheBlock.org

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. The hotline is staffed 24/7 by trained counselors who can offer free, confidential support. Spanish speakers can call 1-888-628-9454. People who are deaf or hard of hearing can call 1-800-799-4889. Help can also be accessed through the Crisis Text Line by texting “HOME” to 741-741.

This report was producer with support from the Credible Messenger Reporting Project, here at the Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence for Gun Violence Reporting.

Tyler Campbell was the lead Credible Messenger community journalist.

Photographer Ronald Gray was also a Credible Messenger community journalist.

Dana DiFilippo was the Professional Partner.

This report was first published at WHYY.org.